The National Cancer Institute (NCI) estimated that in 2016, nearly 1.7 million new

cases of cancer would be diagnosed in the United States. Many of those patients likely

underwent treatments including surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy and radiation.

But what if we could fine tune a way for one's own immune system – our natural defense

against illness – to locate and destroy cancer cells, without the need for invasive

procedures or the harsh side effects of chemical and radiation treatments?

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) estimated that in 2016, nearly 1.7 million new

cases of cancer would be diagnosed in the United States. Many of those patients likely

underwent treatments including surgery, chemotherapy, hormone therapy and radiation.

But what if we could fine tune a way for one's own immune system – our natural defense

against illness – to locate and destroy cancer cells, without the need for invasive

procedures or the harsh side effects of chemical and radiation treatments?

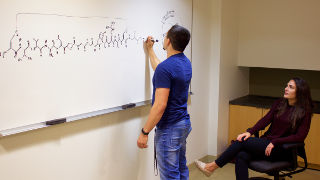

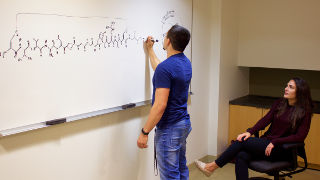

Enter Rachel Montel and Keith Smith, graduate students in the Department of Biological Sciences within the College of Arts and Sciences, who are working on groundbreaking research in cancer immunotherapy that is supported

by a competitive grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Focusing specifically on liver cancer, their research is being conducted under the

supervision of David Sabatino, associate professor in the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, and Constantine Bitsaktsis, associate professor in the Department of Biological Sciences – and in partnership

with Hackensack UMC, with whom Seton Hall is launching its new School of Medicine

in the fall of 2018.

Simply put, some tumors possess a protein receptor called B7H6 that allows the immune

system to locate and attack them until these tumors have been destroyed. Unfortunately,

cancer cells have evolved in clever ways to evade our immune system. In selected cases,

tumors shed this receptor or limit its expression, thereby allowing them to continue

to proliferate. Another unique feature of cancer cells is that they overexpress a

second receptor called GRP78. This receptor is constitutively found on the surface

of many cancer types, including liver cancer, and functions as a biomarker for detection

and treatment. Therefore, Montel and Smith are developing a molecule that would bind

to the GRP78 receptor on cancer cells, while activating our immune system to target

and eliminate the cancer. "Rather than using chemicals to treat diseases, it's always

better to have our bodies do it for us," says Smith, a second-year student in the

master's in biology program. "That's what they're programmed to do."

Simply put, some tumors possess a protein receptor called B7H6 that allows the immune

system to locate and attack them until these tumors have been destroyed. Unfortunately,

cancer cells have evolved in clever ways to evade our immune system. In selected cases,

tumors shed this receptor or limit its expression, thereby allowing them to continue

to proliferate. Another unique feature of cancer cells is that they overexpress a

second receptor called GRP78. This receptor is constitutively found on the surface

of many cancer types, including liver cancer, and functions as a biomarker for detection

and treatment. Therefore, Montel and Smith are developing a molecule that would bind

to the GRP78 receptor on cancer cells, while activating our immune system to target

and eliminate the cancer. "Rather than using chemicals to treat diseases, it's always

better to have our bodies do it for us," says Smith, a second-year student in the

master's in biology program. "That's what they're programmed to do."

"Our grant is of an exploratory nature, meaning that our research is still in the

early stages, but it has shown promise and been deemed innovative, and that's why

it has been funded by the NIH. This has given us further belief that the clinical

application of our approach in the future is a real possibility, positively impacting

the field of cancer immunotherapy," says Bitsaktsis.

The grant, entitled "NK Cell-Dependent Cancer Immunotherapy with Semi-Synthetic Peptide-Protein

Bioconjugates," was approved by the NCI as part of the Omnibus R03 Small Research

Grant Program in Cancer Research. As Sabatino explains, funding for the award is $100,000

for two years of support, including a $10,000 award to Montel and Smith for their

research contributions related to the project. "Considering the NCI falls under the

umbrella of the NIH, which is sponsored by the federal government, these grant applications

are extremely competitive and difficult to receive," says Sabatino. "Currently, the

success rate for this research grant program is only 10%."

The grant, entitled "NK Cell-Dependent Cancer Immunotherapy with Semi-Synthetic Peptide-Protein

Bioconjugates," was approved by the NCI as part of the Omnibus R03 Small Research

Grant Program in Cancer Research. As Sabatino explains, funding for the award is $100,000

for two years of support, including a $10,000 award to Montel and Smith for their

research contributions related to the project. "Considering the NCI falls under the

umbrella of the NIH, which is sponsored by the federal government, these grant applications

are extremely competitive and difficult to receive," says Sabatino. "Currently, the

success rate for this research grant program is only 10%."

The grant also represents an important milestone: this is the first NIH grant awarded

as part of a research collaboration between Seton Hall University and Hackensack UMC.

The team is synthesizing the molecule on the Seton Hall campus, but pre-clinical studies

are being performed at the John Theurer Cancer Center under the leadership of Dr. Robert Korngold, chairman of the Department of Research.

"The type of research we're doing isn't basic research. It isn't so that others can

use it to generate an outcome," says Montel, a first-year student in the Ph.D. in

molecular bioscience program. "It's translational, meaning we're the ones bringing

about an outcome."

"Keith and Rachel are engaged in interdisciplinary collaborative research work that

has allowed them to advance their understanding of basic and translational medical

sciences," says Sabatino. "This type of research exposure is critically important

for our students invested in bio-medical or medicinal chemistry research work. This

project was initially developed in our labs by a small team of graduate (Mariana Phillips,

Ph.D.) and undergraduate (Francesca Romeo and Andrieh Darwich) students that laid

the groundwork for Keith and Rachel. Mariana and Francesca have graduated and are

pursuing research endeavors in the private sector as well as in academia. Considering

New Jersey is a hub for the bio-tech and pharmaceutical industries, the fact that

our students are trained in research work that is akin to the industry standard promotes

their likelihood for success after they complete their degree programs."

"Keith and Rachel are engaged in interdisciplinary collaborative research work that

has allowed them to advance their understanding of basic and translational medical

sciences," says Sabatino. "This type of research exposure is critically important

for our students invested in bio-medical or medicinal chemistry research work. This

project was initially developed in our labs by a small team of graduate (Mariana Phillips,

Ph.D.) and undergraduate (Francesca Romeo and Andrieh Darwich) students that laid

the groundwork for Keith and Rachel. Mariana and Francesca have graduated and are

pursuing research endeavors in the private sector as well as in academia. Considering

New Jersey is a hub for the bio-tech and pharmaceutical industries, the fact that

our students are trained in research work that is akin to the industry standard promotes

their likelihood for success after they complete their degree programs."

Indeed, Montel and Smith are well aware of what the grant could mean for them professionally

– and how it might enable and empower them to continue to push the biomedical industry

forward. While Smith plans to leverage his experience as he pursues a Ph.D. in biochemistry

and eventually teaches, Montel will continue as a clinical investigator, ultimately

setting her sights on congenital disorders. "There can never be too many research

endeavors because you're constantly making advances. Even when you make an error,

you're always learning something," she says. "At the end of the day, I like knowing

that I'm making a contribution to the scientific and medical communities, and to the

general population."